The Valley of Secrets

- Tania Bock

- Jan 13, 2022

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 15, 2022

I read this for the first time in elementary school. I’m not really sure how old I was, but I remember reading it on the old green couch in my living room and in the cracked leather couch of the two-room summer camp I went to. Unlike many childhood books, I know exactly where I got it- I sneaked into my sister’s room while she was at sleep away camp, determined to read her books and finish them before she got back and found out. My sister lives in a different city now, so there’s a lot less sneaking and a lot more just walking into her room and taking stuff. Coincidentally, this time around I did basically the same thing, and though I didn't finish it before she came home for Christmas, I think she is only finding out my (double) theft as she reads this post.

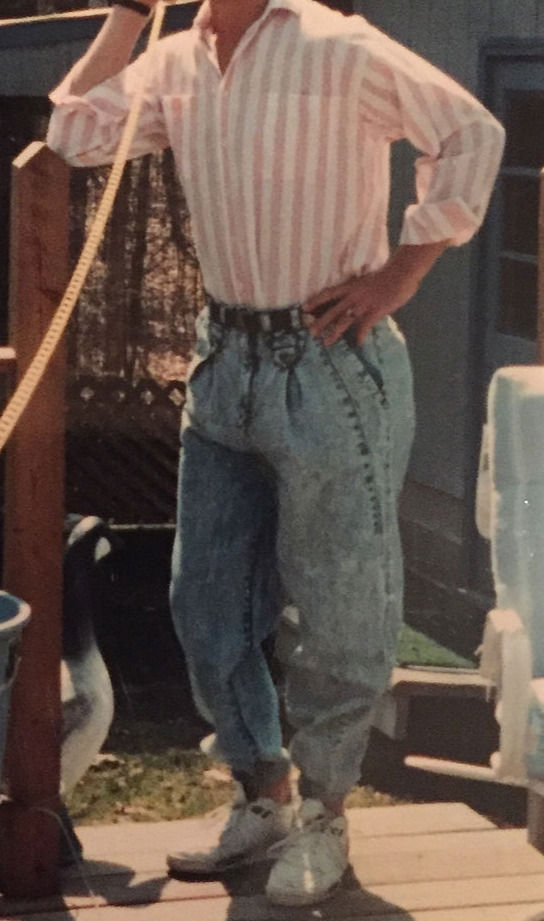

Obviously, this is a children’s book, so I’m not exactly the Target Audience. However, I remember finding this book interesting and magical and mysterious- and I didn’t feel any of those things this time. The book is about a teenage orphan named Stephan, (as a kid, I insisted it was pronounced like “stefan”, because why else would the "ph" be there), who suddenly inherits an estate from a long-lost relative in Cornwall. With a great interest in plants and animals, and having never had any family, Stephen travels to live at the estate, Lansbury Hall. There he lives alone in a big, empty, old house which has no electricity, and is a days walk from the nearest village (he has no car). Also, this book takes place in the 80s, so I always imagine Stephen in acid wash jeans and a nice button down. That’s not relevant to the plot, I just want you to imagine it too.

This is sort of the back-cover summary of the book, but already there are major problems. First of all, where are the adults? Stephen went to Lansbury expecting a friendly, welcoming, well-fed housekeeper or some sort of household staff, and when he doesn’t find them he just... lives there anyway? He tells his foster parents that he is either going to stay with a friend or is going to camp. I don’t remember which, that’s how little significance is given to him just not having any adults around. There are a few throw away lines about how he writes to his foster parents to let them know “camp” is going okay. The inclusion of these lines makes it all the less believable. We never actually meet them in the book, but can they really be that neglectful? Like, they’re not going to call or anything? They’re legally responsible for this kid! And he’s fourteen which is peak dumb-ass years. They should be more concerned.

*Spoiler Warning* Stephen lives alone in this house but sometimes feels like there’s someone watching him. He reads about his Great-Uncle Theodore’s Amazon adventures with the Taluma tribe in the 1910s; A narrative so concerned with falling into the English imperialist idea of “primitive” indigenous tribes that it goes straight into the “noble savage” stereotype- complete with descriptions of their one-ness with nature and polemics about what we “civilized” people have to learn from them. Not that the racism of English imperialism is any better, but in a book about the exploitation of indigenous amazon people and the destruction of the rain forest, you’d expect a slightly more nuanced look at indigenous people.

Anyway, he finds a strange, furry, wounded animal that he names Tig, and nurses back to health. He learns from Theodore’s journal that it’s one of a species he found in the Amazon rainforest called “Bugwomps”. Soon after, he finds hidden valley on the estate, with a cave filled different species of bugwomps and an elderly indigenous man named Murra-yari. Theodore had taken Marra-yari to England when the rest of his tribe, the Taluma, had been kidnapped and possibly enslaved by rubber merchants. Having been brought up at Lansbury Hall, he speaks “very-well spoken and correct English, if a little old fashioned” (270). Yet he also knows how to camp out in a cave for weeks at a time and moves through the forest with grace Stephen could never hope to achieve (it’s heavily implied that this is because Murra-yari has some innate ability to do this, which Stephen does not- take the problem with that as you will).

Obviously I did not like the book. I skipped a whole section in the middle that didn’t really matter, and there was a bunch of stuff at the beginning that I should have skipped too. Part of the problem with this is the writing style. Hussey does this thing where she adds three detailed, connected, but unnecessary adjectives before a noun. Instead of making effective imagery, as it’s clearly meant to, it’s just tedious. To illustrate this, I’ve used this style in this post. If it seemed like clunky writing, imagine a whole paragraph of that sort of thing.

The other problem is psychic distance. This is difficult to explain, but basically, it has to do with how close the narrative is to a character’s direct thoughts. A bare description of an event, without explanation of a character’s thoughts, has a large psychic distance, a narrative that describes a character’s thoughts, though not necessarily in their voice, has less psychic distance, and a stream-of-consciousness novel has almost no psychic distance. As Gardner describes in The Art of Fiction, a common writing failure is

There’s more to this, and the use of psychic distance, but that’s basically it. Hussey maintains the "observing consciousness" filter for much of her writing, but will suddenly drop it for direct thoughts before switching back again. Here is an example:

First she tell us his feelings (frustration) without his own voice, then gives us his direct thought (what could he do?) before flipping back to describing his feelings (upset) in the original distance. It would have been better if we had more of Stephen’s direct thoughts, and understood his emotions through the anger in his thoughts.

It did have a moment of magic, and that was with the book itself. It’s nearly square, which seems like a small difference from the normal rectangular page, but holding it makes you feel like a kid again. It’s kinda floppy, a little big, a bit unwieldy- exactly how every child feels when handling something for grown-ups. There are also beautiful illustrations in this book. Christopher Crump created wonderful prints for each chapter. His style adds to the magic of the book, and what he chooses to draw points to what is significant in each chapter. For a child, these illustrations would alert them to details they may otherwise miss.

I will also say this in favor of Hussey: she clearly feels deeply about her topic. The moral of the book is the destruction of the amazon, and it’s damage to people, plants, and animals. She wants to educate others and inspire them to take action. She even goes so far as to include a bibliography and a list of relevant organizations at the back of the book. Though she often has trouble with this, she sometimes succeeds in conveying her (and Stephen’s) love of nature to the reader. Her downfall comes from her righteous denunciation of destructive practices and “Man’s” exploitation of nature. Chunks of description of Stephen’s thoughts read like a pamphlet handed out by volunteers in the street, and there’s an entire chapter at the end where Stephen does read a pamphlet and react to the statistics. The destruction of the Amazon rain forest and the human rights abuse of its indigenous population are genuine problems, but this book fails to display them urgently to the reader. The strength of fiction comes from its ability to incite the reader’s emotions about unfamiliar events. A story about people actually living in or around the Amazon rain forest, experiencing such devastation, would have a greater emotional impact. Sure, Stephen is angry and frustrated, but his Lansbury estate remains an idyllic Eden. he faces no threat of destruction, so the deforestation feels as distant at the end of the book as it did before reading. You might say “Tania, this is a children’s book, the message can’t be subtle”. Well, I read this as a child and I didn’t pick up on that message at all. All I remembered was the Bugwomps and Murra-yari and Stephen in that big house. I will reiterate: there is no immediate threat, so there is none of the urgency that would make an impression on a child. Her message isn’t palatable to a child, so it goes ignored.

Overall, I didn't enjoy this reread as much as I expected I would. I knew that it would feel different from when I read it as a child, but I was still disappointed with its reread. Still, I think this book could capture a kid's imagination, and allow them to move past clunky writing.

This is book is for a 8-10 year old interested in nature.

Background photo: "Ghost House" by Florian Olivio

"1980s fashion with acid-washed jeans.jpeg" by Abroe23 can be reused under (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Comments